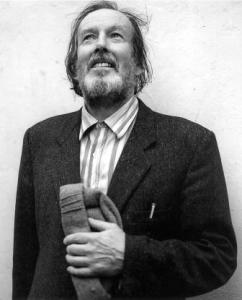

Roger Mayne

2006 Honoree / Achievement In Documentary

Roger Mayne, photographer, (1929-2014) had a highly original eye for elusive detail. Self-taught, he was passionate about photographing what he knew – most famously, inner London. His skill in absorbing the radicalism of post-second world war “humanitarian photography” and interpreting it with artistic vision established him as one of the 20th century’s leading photographers. It also made him influential in the development of photojournalism.

His photographs of west London street scenes in the 1950s captured members of the first generation to be identified as “teenagers”. The W10 series, shot mainly around Paddington, contrasted young people’s exuberance with the urban dereliction they inhabited. For five years from 1956, Mayne focused obsessively on Southam Street, later to be demolished as part of a slum clearance programme. The street takes on a life of its own through its young residents: there is a kind of innocence in the scruffy juveniles fighting with wooden swords or tipping each other out of broken prams. It is hard to relate these youngsters, boys in shorts and unlaced leather shoes, girls with school-uniform gingham frocks and kirby grips pinning back their hair, to subsequent generations of teenagers.

Fashion burst suddenly upon Mayne’s subjects, with teddy boys in their satin lapels and teenage girls who still spent all day with hair in rollers under knotted turbans. The historian Mark Haworth-Booth said: “Mayne was very quick to seize on Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Images à la Sauvette [translated as The Decisive Moment, 1952], which became his inspiration for Southam Street, and in the 1950s he was also in contact with the American Paul Strand.”

The decade proved to be an awkward period for photojournalism. The pioneering interwar years of the medium, following closely upon the invention of the high-speed Leica camera, had passed, and the reinvention of British photography by figures such as Don McCullin, David Bailey and Brian Duffy had not yet begun. Mayne’s contemporary influences were as much among the St Ives school of artists, whom he visited in 1953. He became friendly with Roger Hilton, Terry Frost and Patrick Heron.

According to his New York gallerist, Tom Gitterman: “Mayne consciously printed with high contrast to emphasise the formal qualities in his work, and increased the scale of his prints to have a further dialogue with the painting of his time.”

His eye had always been for depth and detail, and he demonstrated an awareness of fine art when he photographed the broad sweep of serried roofs in Cornwall (St Ives, 1953); the Skylon, the structure that came to symbolise the Festival of Britain, against a bleak sky (1951); and a toddler straining against the wind on the concrete flats of Plymouth Hoe (his daughter Katkin, in 1968). Katkin and his son, Tom, became favourite subjects, even when the focus was elsewhere – for example, in the ostensible portrait of a stone lion in Trafalgar Square, perfectly brought down to scale by a pram parked in front of it with Tom’s eyes peeping over the side (1970).

Children feature frequently in both his rural and urban imagery: Mayne was dedicated to the whole subject of childhood. He worked closely with the pioneering sociologists Peter and Iona Opie, for whom he documented children at work and in the playground, and provided the cover and a substantial amount of material for the Combined Societies touring exhibition in 1954, specifically a panel on children snowballing and another of kids playing in a bombed-out shell of a house in Bermondsey. The radical intent of the Combined Societies group, which broke the monopoly of the traditionalist Royal Photographic Society to promote the “new and progressive”, accorded him both free rein and recognition in the early 50s.

He admitted that his photographic interest in the boisterous company of street children sprang from a quest “for the kind of childhood I didn’t have”. The son of Dorothy (nee Watson) and Arthur Mayne, he was born in Cambridge and sent away “too young” to board at Rugby school, where he found himself at the bottom of the pecking order. During his years studying chemistry at Balliol College, Oxford (1947-51), he felt he was mixing with those he was least interested in meeting.

He began taking photos at Oxford, and in 1951 managed to place a four-page spread on Between Two Worlds, an experimental ballet performed at the university, in the mass-selling weekly magazine Picture Post. It was an unusual press debut for a photojournalist who would go on to publish regularly in the Sunday Times, Time and Tide, the Observer and New Left Review. During his principal period in photojournalism (1957-62), he was also commissioned by the Chicago Sun-Times and the Times, and his photographs appeared in Vogue, Queen and Peace News, to which he also contributed a number of articles.

The first international exhibition to showcase his work was Otto Steinert’s Subjective Photography 2 at Saarbrücken, Germany (1955). Within six months, he had a solo show at George Eastman House in Rochester, New York state, to which he returned with the group exhibition Photography at Mid-Century. This prompted the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London to mount his work (1956), and both the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Art Institute of Chicago to start acquiring it.

The main body of his work is now housed in the Fox Talbot historical centre, in Lacock, Wiltshire, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the University of Parma and the Folkwang Museum, Essen. Subjects include such disparate topics as landscape photographs of Devon and Dorset, an anthology of seashells, and street photography from Corfu and Rhodes, as well as his London reportage.

Mayne was a lecturer at the Bath Academy of Art (1966-69) and, when writing as an art critic, referred repeatedly to a “false state of photography”, which refuses to admit it remains properly an art form. As a practitioner, he saw himself as having come late to the Cartier-Bresson idiom, a consolidator rather than an innovator. They shared the style of “concerned” social documentary photography, taking street pictures with human subjects and applying a classical black-and-white composition to them.

In 1986, Haworth-Booth, the V&A’s then director of photography, curated The Street Photographs of Roger Mayne. The subsequent South Bank Touring Show, visiting 24 venues, led to Mayne’s work being represented by the Zelda Cheatle Gallery, London, which revised and reissued the V&A catalogue, containing the first in-depth critical and historical appraisal of Mayne’s output. In 2004, the National Portrait Gallery showed a selection of his portraits, some of them of theatrical subjects. His work has since featured in Art of the 1960s: This Was Tomorrow at Tate Britain (2004); How We Are: Photographing Britain, again at Tate Britain (2007); and Roger Mayne: Aspects of a Great Photographer at the Victoria Gallery, Bath (2013).

Roger Mayne died 7 June 2014, at the age of 85. He survived by his wife, playwright Ann Jellicoe, Katkin, Tom and his grandchildren, Zoe, Leon, Poppy, Iris and Ralph.