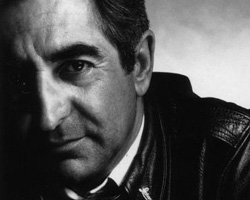

Jim Marshall

2004 Honoree / Outstanding Achievement In Music Photography

It can be said that Jim Marshall invented rock music photography. To many, his images define an era. Marshall grew up in San Francisco’s Fillmore district, and by the early 1960s, was exploring the beatnik clubs in North Beach with a used Leica camera. He photographed some of the top jazz and blues performers of the day, including John Coltrane, Big Mama Thornton, and Muddy Waters. His stark black and white photos showed performers in a new light, and Marshall’s career was launched.

Marshall later moved to Greenwich Village in New York City, where he shot folk performers in the bars and coffee houses along Bleecker Street. One of his subjects was a young Bob Dylan, whom he photographed when the music legend was a relative unknown. Marshall loved the scene: the intensity of the performances, the smoky clubs, the rabid fans, and most of all, the music. He returned to San Francisco just in time for the late-60s revolution, when the city became a hippie mecca, and a focal point for the new music scene. Marshall was there in the thick of it all, and his photos of music icons Janis Joplin, the Grateful Dead, the Jefferson Airplane, the Rolling Stones, and the Beatles, exemplified a phenomenal era in American pop culture.

The performers granted Marshall unlimited access to them, treating him as if he were almost a member of the band. This intimacy resulted in his capturing of images that revealed the musicians in all their humanity – flaws and weaknesses exposed, passions and vulnerabilities revealed. When the Beatles played their final live concert at Candlestick park in 1966, Jim Marshall was the only photographer allowed backstage during the show, and when the Jefferson Airplane began playing gigs, Marshall was the first photographer to discover them. When the Rolling Stones started their “Exile on Main Street” tour in 1972, Marshall flew with them, the only photographer allowed on the band’s jet.

By the mid-70s, however, the door started to close. Record company executives, wanting to keep a tighter hold on their groups’ images, began restricting photo access and photo ops. For Marshall, lacking a direct conduit to the musicians represented disaster. However, he resurrected his body of work in the 1980s, and introduced it to a new audience. The recently published “Not Fade Away: The Rock and Roll Photography of Jim Marshall,” collects his best images from this important era.