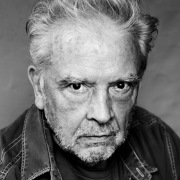

David Bailey

2006 Honoree / Achievement In Fashion

David Bailey, CBE, is an English fashion and portrait photographer whose image bank is in our DNA. Anyone even slightly acquainted with the Sixties has Bailey’s images of Shrimpton, Jagger, Lennon & McCartney and the Kray twins somewhere imprinted on their consciousness. It’s impossible to look at them without feeling the presence of their creator at your shoulder. Bailey, the quintessential wide-boy photographer whose rise exemplified the period’s social revolution, who was, proverbially, as famous, glamorous and sexy as the people he photographed.

Graduating from being an assistant with fashion photographer John French in 1959, Bailey began the 1960s with a contract with Vogue to become the decade’s iconic chronicler with two defining portrait publications David Bailey’s box of pin-ups (1965) and Goodbye Baby and Amen (1969). They focused on a new social order that evolved from the decade of change. Bailey was a leading figure in the Swinging Sixties London scene and provided some of the inspiration for the role of the photographer, played by David Hemmings, in Antonioni’s cult film Blow Up (1966.) Bailey had his first Museum exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in 1971.

Over the decades since his Sixties heyday, Bailey has become a fixture in British culture. He’s directed commercials and documentaries, featured in advertising campaigns, seen his lifestyle used as the inspiration for Michelangelo Antonioni’s seminal 1966 Swinging London film Blow Up, and his early life with Shrimpton portrayed in the 2002 BBC film We’ll Take Manhattan. The cachet of his name has never waned. Yet through all this he has remained an essentially pop figure.

Bailey has never wanted to be seen simply as a photographer, but as a total creator like his idol Picasso. Yet while he’s made films and exhibited his paintings – in a broadly pop idiom – they’ve failed to make anything like the impact of his photographs, the best of which retain extraordinary freshness and power.

“I’m interested in people,” he says, “and whatever you see in the photograph, whether you call it glamour or drama or edge, it’s already in that person. I can’t put it there. It’s finding it and bringing it out. I can see the moment when they look the way I want them to look, or the way I think they should look or they don’t want to look, or whatever. It’s the moment that counts. It’s the only thing we’ve got in life really, and nothing captures it the way a stills camera does.”